ADCIRC has been important in helping the media communicate the likelihood of flooding threats, and public officials use ADCIRC’s models to make decisions about evacuations when storms loom.

But preparing for the impact of hurricanes goes far beyond evacuation and rescue. Government officials use data that the ADCIRC system collects during storms to understand how infrastructure failures occurred so that they can better fortify communities in the future, and researchers rely on ADCIRC data to study the long-term impact weather disasters have on people.

It’s these applications that make Luettich’s work perhaps even more critical as climate change spurs discussions about how to prepare for and recover from the most damaging weather.

Storm forensics

Preparing for future storms requires a thorough understanding of the past. Conversations following hurricanes often fixate on wind speed and category ratings, but the more important questions focus on water and infrastructure. Where did the water go? How long was it there? How did it get there? Were there structures, such as a levee, that failed? How high was the water when the failure occurred?

“Those are hugely different and important questions,” Luettich said. “It’s like when an airplane crashes and the National Transportation Safety Board tries to figure out what went wrong. They pick up all the pieces and look at it and use all of the knowledge and tools to avoid that happening again. ADCIRC gives us those tools for storms.”

After Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast in 2005 and caused more than 1,800 deaths, the devastation was so vast that it was difficult to determine exactly what went wrong. Well before the storm, Luettich had set up data collection points in New Orleans, and so ADCIRC held critical information to answer the questions of precisely where and how failures had occurred. In Katrina’s aftermath, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers called on Luettich for his expertise in what he referred to as a “massive forensic study” of the storm.

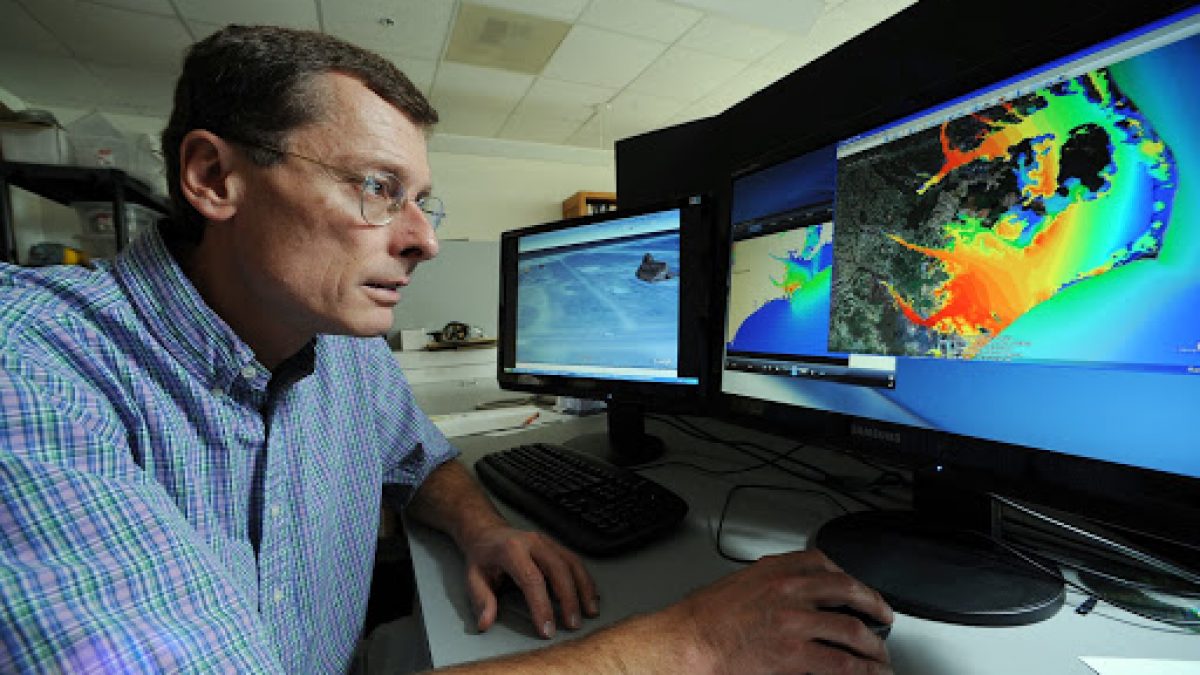

Rick Luettich at a levee in Louisiana. Luettich’s work helped the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers redesign flood protection systems around New Orleans following Katrina. (Photo credit: UNC IMS.)

“We learned that many of the floodwalls failed at far below their design capacity, so then the Corps of Engineers went back in and tried to understand why that was,” Luettich said. “Had we not developed the model and been working in the area so we could build up all the underlying databases required to actually use the model, then it would have been impossible to have contributed to the response.”

Luettich’s work informed the Corps of Engineers’ design for a new flood protection system around greater New Orleans. Congress also wrote ADCIRC into post-Katrina legislation requiring the Federal Emergency Management Agency to redraw its flood maps throughout coastal areas, and Luettich helped study coastal areas throughout the East Coast.

Forensic examinations of storms are also a valuable tool in evaluating and improving the ADCIRC model itself, and Luettich embraces the opportunity to compare what actually happened during the storm with ADCIRC’s predictions.

“You can think about these things theoretically and gain knowledge and write papers,” Luettich said. “For me, what’s exciting and really significant is to then turn around and start using these tools to solve real problems. You find that some of the initial things you conceptualized didn’t necessarily match up with the way things worked, and you are in a great position to continue to improve.”

Helping people recover

Following a major storm, damage to structures and even loss of life can be tabulated with some degree of accuracy. But after winds calm and floodwaters recede, less is known about the long-term impact on people. When a community suffers widespread flooding, what are the costs for displaced families? How is the local economy affected? How are schools and children affected? What are the challenges for the elderly?

Assessing the true toll of a storm becomes more complex when examined through this lens, and unlocking answers to these questions can help officials deploy resources and services that enable a more complete recovery. Luettich’s work has been instrumental in helping researchers pinpoint areas that have been hit by storms, and he has partnered with the Carolina Population Center on a project called Dynamics of Extreme Events, People and Places that studies the aftermath of disasters in eastern North Carolina.

“There’s a hub of this project that we call, ‘Where the Water Went,’” said Elizabeth Frankenberg, director of the Carolina Population Center. “[Luettich’s] models are really good at telling us where water went and how long it stayed. And that gives us a detailed picture of what people were exposed to.”

A hydrologic technician measures flooding in eastern North Carolina during Hurricane Florence in 2018. (Photo credit: Laura Lapolice, USGS)

In surveys and interviews, Frankenberg’s team gauges social, emotional and psychological impacts on people. Partnering with Luettich, they can differentiate between communities where flooding swept through quickly versus those where water remained for days.

“Both are incredibly destructive, and we use ADCIRC data to understand the nature of the event,” Frankenberg said. “We want to be able to link types of events to the kinds of impacts and the duration of those impacts.”

Luettich welcomes the opportunity to work with other researchers, including students, and points to the collaborative environment at Carolina as an important component in helping our state prepare for future storms.

“This is what I think is really exciting about what we are doing today in collaboration with others that know the social science and people side of this,” Luettich said. “If the past is any indication of the future, with climate change upon us and things all around us changing, the need has never been greater for a group of scientists who are working with this as their mission.”

Luettich’s work has received funding through the Department of Homeland Security. To support research that protects our coastal areas, consider

a gift to the Institute of Marine Sciences.