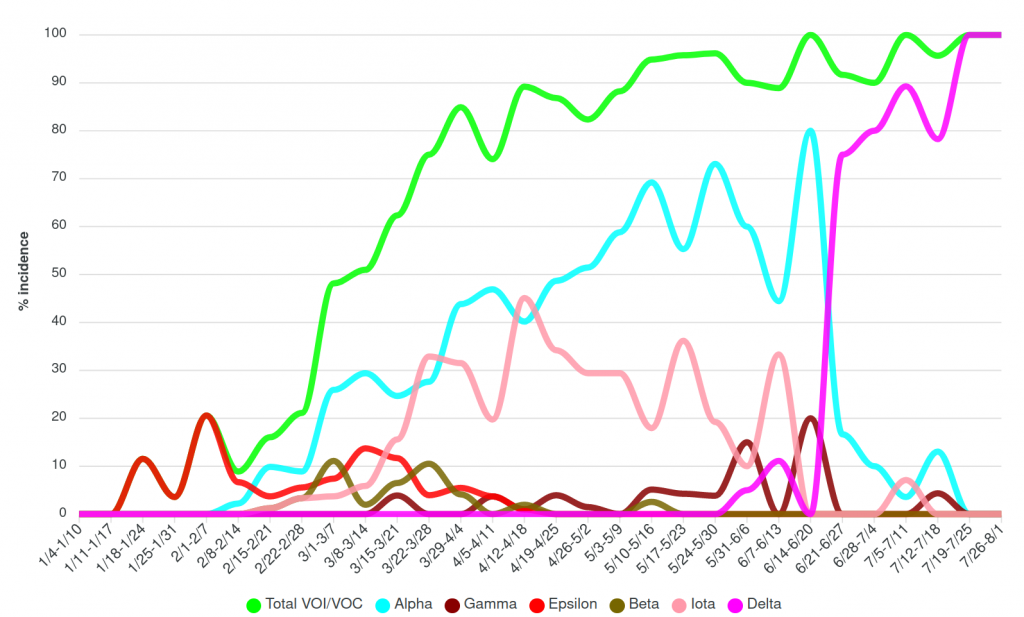

“The transparency of the data on this public facing website is critical,” stressed Professor Melissa Miller, Ph.D., director of the Clinical Microbiology and Molecular Microbiology laboratories at UNC Medical Center. “Our clinicians look at it daily; I get emails about it. It is definitely a service to our professional community and to public health and the community at large.”

Beyond its clinical use, Miller uploads the data to the state’s communicable disease branch, providing state health officials with accurate, up-to-the-week snapshots of what’s going on in North Carolina.

“As a component of a broad health care system, we have specimens coming from hospitals across the state, so our data represent more than just our surrounding counties,” she said. “Policymakers and epidemiologists can link those data to GPS or community specific data, like zip codes, and they know the vaccination rates in counties across the state. They can then take action, really target those areas where a variant of concern is spreading.”

For example, as the state is starting to see more of the Delta variant, which is of concern because it is more highly transmissible, one excellent intervention that Miller mentioned is to try to improve the vaccination rates in the areas most affected.

“As you’d expect, we’re seeing more COVID in the areas that have lower vaccination rates, and it’s important to look at what the variants are,” Miller said. “The more you have transmission of the virus, the more likely it is for a new variant of concern to emerge. When you increase vaccination rates, you decrease the potential for emerging variants.”