Advancing Cancer Research and Care Across Carolina and the Globe

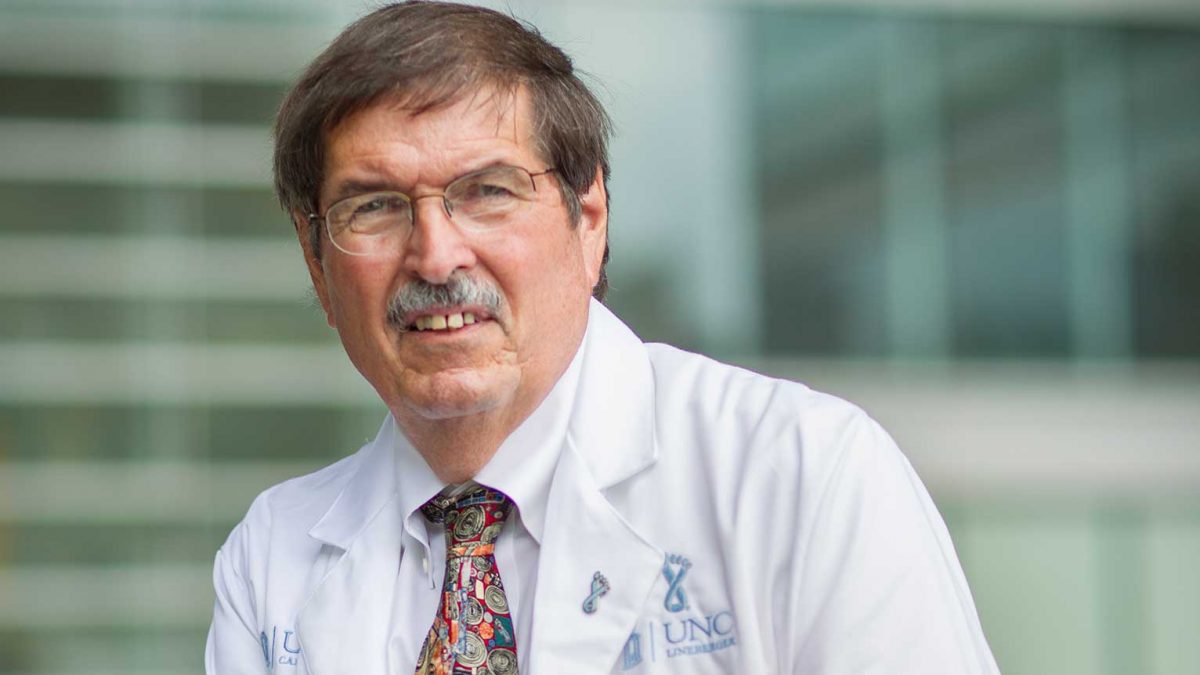

Published on August 19, 2019As a nationally recognized cancer researcher and current director of UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Care Center, Shelton “Shelley” Earp is as comfortable in the lab as he is cheering for the Tar Heels in the Dean Dome.

As a nationally recognized cancer researcher and current director of UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Care Center, Shelton “Shelley” Earp is as comfortable in the lab as he is cheering for the Tar Heels in the Dean Dome.

There’s no place that Shelton “Shelley” Earp, M.D., feels more at home than at UNC-Chapel Hill. As the director of UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center and an integral leader in cancer care for the past 40 years, Earp is just as comfortable in the lab as he is cheering for the Tar Heels in the Dean Dome.

Growing up in Baltimore, Earp decided to become a doctor, attending Johns Hopkins University as an undergraduate, then making the decision to come to Chapel Hill for medical school, driving up the Franklin Street hill for the first time in 1966. Once on the ground at Carolina, Earp pursued his undergraduate interest in how cells behave, both in healthy and cancerous tissues. He was influenced to seek an academic career by Robert Ney, M.D., the chair of the Department of Medicine and the head of the endocrinology division, who served as his research mentor.

“After a tour in the army, serving in the medical corps, I came back to work with Dr. Ney in 1974 and have stayed ever since,” Earp said. “I was lucky enough to have a research lab in the Army that helped jumpstart my molecular biology work.”

It didn’t hurt that his wife, Jo Anne, a graduate student at Hopkins’ School of Public Health, whom he met during his time in the service, was also embraced by Carolina. Offered a position in public health, she eventually rose to become chair of the Department of Health Behavior in 1996. “We’ve been extraordinarily happy living in this special place, with both of us having rewarding professional lives at Carolina,” he said.

That was just the beginning of Earp’s career in cancer. In the late ’70s, Joseph Pagano, M.D., former director of UNC Lineberger, asked Earp to join the cancer center. “He asked me to become involved because I was a physician, but I also had a basic research interest in how cancer cells are altered,” Earp said. “There were not many oncologists here, but Joe [Pagano] was prescient in looking to develop physician scientists interested in studying how cancer evolved and was treated.”

After all these years, Earp continues to feel as at home in the halls of Carolina as he does with his family. He has two adult sons living in Georgia and California. His care and concern for cancer patients, as well as the research that can make a difference in their lives, hasn’t wavered.

At the helm of UNC Lineberger, Earp is dedicated to recruiting and retaining the best and brightest minds in cancer care and research. He believes UNC Lineberger is the perfect place for amazing insights into cancer care and treatment because collaboration is so prized by the faculty and staff.

“We value the low stone walls that Carolina is famous for. That attribute is so much better than being siloed into one’s own area and protective of one’s own advancement. UNC is exactly the opposite,” he said. “In my clinical and research career, I have learned so much from so many colleagues, both young and old. One secret is having the good fortune as a cancer center administrator to help recruit a cadre of talented young researchers who have developed over the years. Many have become national leaders in their own right. Hopefully, I have helped to advance their careers, but they’ve taught me so much — new approaches, new technology and new ways of looking at problems. We can tap a plethora of intellectual resources in the cancer center and in the broader University; ideas and technologies come in so many flavors from so many directions.”

Cell culture room at the UNC Lineberger Advanced Cellular Therapeutics Facility

One new area that Earp is excited about is progress in cellular immunotherapy, which involves using patients’ own immune cells to fight their cancer. UNC Lineberger is one of only a handful of places in the country that were early adopters of immunotherapy, moving forward by recruiting world-class minds and constructing a Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) facility in 2015. The GMP facility allows patients’ immune cells, isolated in the hospital, to be amplified by the millions, armed with a cancer-finding gene, and prepared for re-infusion back into patients, ready to fight their tumor. “This FDA-inspected and approved clean room space allows us to advance human therapy in a way that I thought was only possible in Sci-Fi novels,” Earp said.

Another area where UNC Lineberger is making strides is in clinical immunotherapy trials. Earp stressed that North Carolina residents no longer need to travel outside the state for the latest in cancer advances, because UNC Lineberger has the capability to serve them.

“With University Cancer Research Fund investments, we were able to institute the program. We are now one of the larger academic units in the U.S. capable of doing novel T-cell immunotherapy for our patients,” Earp said. “We are the only place in the Southeast that has this full capability to manufacture viruses, allowing UNC to test new targets, even pioneer work in new cancers with engineered cells given back to individual patients. Our success is demanding that we grow the program by expanding our GMP capacity.”

After the GMP facility’s expansion to serve patient and research needs, Earp is eager to launch more chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) clinical trials, bringing therapy to more patients and targeting new diseases. New trials on the horizon include research on solid tumors, such as ovarian and pancreatic cancer, as well as glioblastoma and pediatric neuroblastoma.

“All of these diseases are on our radar,” Earp said. “Expanding the patient-capability of the GMP facility offers many opportunities for UNC researchers. For example, in cancer, we plan on expanding to other immunotherapies, such as therapeutic cancer vaccines and innovative ways of doing bone marrow transplants that allow doctors to arm donor cells to get rid of the patients’ remaining cancer cells after their transplant.”

Earp and UNC Lineberger leadership are looking ahead at the variety of resources and programming available for patients and their families, as well as research advances happening daily that allow for superior patient care.

“The bedrock of our mission at Lineberger is combining great, patient-centered treatment with nation-leading research innovations and compassionate care through our Comprehensive Cancer Support Program for patients and their families,” he said. “We look at what we can do for patients now, using the best forms of cancer diagnosis and individualizing therapy.”

Personalizing cancer treatment for each individual patient is a hallmark of the UNC Lineberger clinical teams, something that often begins with clinical trials that examine how patients can be treated most effectively with the lowest levels of chemo or radiation necessary.

“We are constantly asking ourselves ‘How can we reduce the invasiveness of surgery and get patients back to their former lives faster?’” Earp said. “Everything has to start with the patient, but when the patient appears to be out of options, we ask ourselves how we can deploy the brain trust, UNC’s research intellect, to create new, successful therapies.”

As the state’s only public comprehensive cancer center, UNC Lineberger has a mission to serve the people of North Carolina, and Earp said they are regularly looking at how community interventions can help prevent cancer, how early detection methods can be improved and how these ideas can serve people in the state, including everyone from urban populations to rural areas.

Earp believes that “real world” data collection across the state and sophisticated analysis can help UNC Lineberger better serve North Carolina. Faculty use the data to spot areas of North Carolina where access to healthy foods like fruits and vegetables is limited and obesity is high or where effective screening for early detectable cancer is low. Researchers are also looking for areas where care delivery is slower to initiate. Earp said the cancer center is also working on spotting trends in youth smoking and vaping and where rates of cancer prevention vaccine uptake are low.

“We are constantly upgrading technology for early detection and prevention of cancer, as well as how to treat the many forms of cancer we encounter in the clinic or hospital with precision,” Earp said. “Our clinicians are guided by the mantra of what is the most effective therapy and, if cancer recurs, how do we work with our primary partners, our patients and their families, to determine the best course for treatment.”